On October 24, Layi Wasabi, a popular Nigerian skitmaker, posted his first video on YouTube. This, in many ways, was a departure from the style and format that the creator had become known for. His videos hardly ever lasted beyond 3 minutes. But this time around, he was pushing boundaries to create a series of short films over 7 minutes long.

The video series features his popular character, The Law, a bumbling lawyer who often finds himself in outrageous situations. But Wasabi’s switch to YouTube isn’t just about trying out new material; it’s a move to a platform that several creators believe offers greater monetization potential, creative freedom, and stability.

Layi Wasabi, whose real name is Isaac Olayiwola, got his start posting skits on Instagram while studying Law at Bowen University in Southwest Nigeria. In 2021, a skit he made about blocking his mom on WhatsApp went viral, bringing him into the limelight. Building on this initial success, he created characters like The Law, Officer Robert, and Mr. Richard, whose comical misadventures and exaggerated personas repeatedly captured audiences. His popularity surged, leading to industry recognition with awards at the Trend Up Creator Awards—one of Nigeria’s first influencer award shows— in 2023 and the African Magic Viewers’ Choice Awards (AMVCA)—the continent’s top movie industry award show—in 2024.

Wasabi’s move to YouTube aligns with a broader trend of Nigerian creators who got their initial breaks on short-form video platforms like Instagram and TikTok now gravitating toward YouTube. Fellow Nigerian creators like Shank Comics, Gilmore, Broda Shaggi, and Justin Ug have also started making YouTube-native content, taking advantage of the platform to reach more global audiences. YouTube also comes with promises of a different kind of revenue stream.

Not all creators turn out fine. Not all become successful. But as with many things in life, success often fuels the narratives of history and innovation. Few remember the failures. We canonise the success stories because they’re more attractive, but they lure us into confirmation bias.

This bias tilts our gaze towards the Mr Beasts and Sisi Yemmies of this world and makes us wonder, what if more people could be like them? We don’t ask ourselves enough, how many people can be like them? Do we have enough attention, the currency with which the creator economy is built, to go around? Can our finite collective bandwidth accommodate all that is possible to create?

These questions have interesting implications, some of which we will get to later. Chief among them is that we cannot effectively build longstanding structures for the Creator Economy if we don’t understand the possibilities and potential size of the market. And we can’t fully understand either until we consider the creator lifecycle.

Hugo Amsellem, a VP at Jellysmack, divides the creator lifecycle into four stages: Attention, Trust, Commerce, and Ownership.

At the Attention stage, the goal is to create content that reaches as many people as possible. Here, the creator is growing and renting their audience via their own channels (website, newsletter, community) or third-party channels (social media, video hosting platforms, etc.). The main ways to monetise at this phase are advertising, brand deals, and affiliate marketing.

In the next stage, Trust, the goal becomes owning and retaining the audience. This allows the creator to potentially monetise via memberships, patronage, and donations (I’d add subscriptions here, too). The next stage is Commerce, where the creator has built a trustworthy relationship and connection with their audience that allows them to sell physical or digital products. (At this stage, the creator is no longer just running a media entity but also an e-commerce firm.) The final stage in the lifecycle is ownership. Here, Amsellem says the goal is to share future financial upsides with their audience, including monetising through equity, stock options, and tokens.

Amsellem’s examination of the creator economy leans toward video creators and already influential figures, as we can see in his examples, like Mr Beast, Kylie Jenner, Tim Ferris, and Portugal. The Man. While I don’t think this is the best lens through which to view the creator lifecycle – because it skews reality and shapes the narrative to favour the roars – it’s still useful for helping us think through this subject conceptually.

However, to see this more specifically, we need to consider the possible outcomes of creators’ careers and then use that to chart the course of their lifecycle. Once we do this, we get a sense of what anyone building for this industry needs to consider in the long term.

For the sake of this conversation, we’re charting the course for a creator whose path to success is primarily content creation, not creators who were first influential or successful for other reasons and then leveraged that fame to build an adjacent career. This is also limited to creators whose mediums are primarily digital.

Every creator’s journey begins when they decide to test the waters. At this stage, they’re most concerned with figuring out what they want to create, what the audience likes, and how often they need to serve that audience. Most beginners never continue, or they start but can barely keep up. Eventually, they fall by the wayside.

For those with the fortitude to keep going, their focus is on getting the flywheel in motion. Their goal is to grow their audience and gain more traction and credibility. While some at this stage attempt to monetise and are lucky to, this is hardly their biggest concern.

Very few make it past Inception. They quickly discover that getting anything off the ground is challenging, especially in a world where everyone thinks they can do it.

If one million creators started this journey with us, only 100,000 make it past the first stage.

Now, the flywheel is in motion, and the creator’s work is gaining more traction. More people are noticing and supporting them. They finally have some credibility with their community.

This stage presents a different set of problems: audience retention (in addition to the constant need to grow) and monetisation. The better they get at growing and retaining their audience, the more likely they are to monetise.

Most creators remain stuck in this phase because they think it’s all there is. Some stay here for as long as possible because moving forward requires more than they’re willing to give. It also requires asking questions such as how long they want to be creators, how big they want to become, what the potential size of their market is, and how far they’re willing to go to break new ground.

Of the 100,000 creators who made it to this stage, 95,000 either remain here or fall off, and only 5,000 make it to the next stage.

Creators who get to this point have grown and are making a significant income, but they have the urge to be bigger. They want to feel more secure. They’ve done well so far, but they realise they now need to bring more people into their process. Video creators will hire production assistants. Writers will hire researchers and junior writers. Podcasters will hire more writers and producers, and so on.

They have a new, unfamiliar set of problems: talent acquisition and human and financial resource management. They either become full-blown business managers or get some help. Then they have more people to worry about and, ideally, need help handling organisational functions like sales, accounting, HR management, etc.

Most of our 5,000 creators remain at this stage until they run out of gas, drop down the pecking order, are replaced by hotter prospects, or pivot into other career paths. For many, this is the final step in their career. For a select few, it is the penultimate.

This is the final stage for creators, at least for those who choose to get here. They’ve entered wholly into celebrity (and, sometimes, cult following) status. They’ve gotten rich by leveraging their audience, but they know they won’t be hot forever, so they need to think beyond themselves.

Here, the focus is longevity. How can they achieve more (or more of the same) with less effort? How can they invest in projects outside the scope of what made them successful? How can they channel their fame into long-lasting wealth? How can they build considerable passive income?

This is when we start seeing creators launch venture capital firms, restaurants and hospitality brands, clothing and fashion lines, make-up brands, production companies, creative agencies, etc.

Of the one million creators who started this journey with us, only ten (or fewer) make it to this stage.

Now that we’ve examined the creator lifecycle, what are the implications? What does this mean for creators and the companies building for them?

Each phase of the creator lifecycle comes with different pain points, each pain point presents different economic opportunities, and all these opportunities hold a variety of potential returns on investment.

Companies building for only one phase are more prone to market instabilities, all of which are determined by supply and demand. For example, because it has become easier to create content, there is minimal upside for products whose only function is helping creators produce content. Therefore, the hard work isn’t in creation. It’s in distribution and monetisation.

So, companies lowering the barriers to content creation must also think deeply about helping their creators distribute, grow their audience, and possibly monetise. This is why I’m a massive fan of Substack’s recommendation feature, Ghost’s variety of platform and community-building options, YouTube’s advertising revenue programme and network effects, Twitch’s platform and audience-building opportunities, and ConvertKit’s sponsorship programme. One can essentially build entire media companies on the infrastructure and mechanisms these platforms provide. They're all building to cover the first three phases of the lifecycle.

Creators evolve when they outgrow one set of problems for another. Each new phase comes with different priorities.

A creator who needs to expand their operations isn’t in the same category as one who wants to grow their audience and monetise. One faces a functional capacity problem, while the other faces distribution and revenue problems.

The creator who has to worry primarily about operational expansion already generates more revenue than the creator who just wants to grow their audience and make money. Therefore, it makes economic sense for a company to focus more on the former than on the latter. However, is there a compelling case for any platform to devote its product development resources to this? I don’t believe so. The companies that identify and attempt to solve this problem do so by creating knowledge banks or capacity development programmes.

YouTube might not be able to help creators scout and hire new talent, but it can create programmes that give them the knowledge required to make those business decisions. ConvertKit might not be able to connect individual creators with potential sponsors, but it can create a sponsorship programme they can easily plug into. This particular point is why I understand Substack’s decision to scale back on its writer benefits, at least until they can be more favourable to its bottom line.

There are opportunities to help creators evolve, but those opportunities are sometimes unaligned with a platform’s core operations and business model. Still, not catering to those creator needs could lead to potentially losing them to direct or indirect competitors. It's client relations 101.

There are many more implications of thinking about the creator economy from the perspective of this lifecycle, and these are just a few.

What a creator needs at the beginning of their journey is hardly what they need in the latter stages. What they need three years into their career is probably not what they need by year seven. Understanding this influences how we account for the size, heterogeneity, and possibilities of the market we’re building for.

I've published Communiqué at no cost for over two years now. In that time, it has grown to over 32,000 subscribers worldwide. The beauty of the newsletter is the quality of insight it provides, and I'd like to keep publishing it at this level. Your support makes that possible.

]]>

My biggest fear launching this newsletter in April 2020 was how it would end. I’ve played out several scenarios in my head, often with a tinge of fear.

In one scenario, I’m many months into a premium model where everyone pays to read most of the essays, but I’m at my wit’s end. I’m jaded, and my brain is scorched as desert sand. Still, I can’t stop. I must keep going. I have an obligation to the people who pay me to churn out insights.

In another scenario, the newsletter remains “free”. I put free in air quotes because is anything ever really free? Every ten minutes someone stops to read the newsletter is ten minutes of their life they could’ve spent doing something else. That’s not “free”. Every edition of the newsletter I publish is at least ten hours of my life I could’ve spent doing something else. That’s not “free”. But for now, let’s stick with the word. In this scenario where the newsletter remains “free”, I’m a prisoner to the schedule. Weekly, bi-weekly, monthly, it doesn’t matter. A schedule is a schedule, and it ruthlessly demands commitment.

In the third scenario, Communiqué evolves. What was once a newsletter grows into something bigger, something that requires more hands than I currently have. In this scenario, Communiqué exists in multiple forms – as a newsletter, videos, podcasts, illustrations, the whole gamut of content formats, most of which are produced by people not named David Adeleke. This is, perhaps, the likeliest outcome. But arriving at that point won’t be easy, and until then, there’s a cross to carry.

Like me, every creator fears the day their creative juices run out. One of my favourite examinations of creator burnout happens in this New York Times piece by Taylor Lorenz.

She opens with quotes that perfectly sum the conversation up: “I feel like I’m tapping a keg that’s been empty for a year,” says Canadian TikToker and model Jack Innanen. “I get to the point where I’m like, ‘I have to make a video today,’ and I spend the entire day dreading the process.”

Creator burnout is a problem that many don’t often admit publicly. In 2018, several major YouTubers became victims of burnout and had to step away from the platform for a while, primarily for mental health reasons. In 2016, PewDiePie briefly quit vlogging on YouTube for the same reason. The pressure to constantly create and put out content weighed heavily on him. He eventually returned, but still, his public admission of burnout was a landmark event.

Another TikToker, Zach Jelks, told The New York Times, “I do worry about my longevity on social media. People just throw one creator away because they’re tired of them.”

And I know a few creators in my circle who’ve had to give up what they love doing so much or at least are on the edge of giving up because their tank is empty.

Creator burnout is the flip side of the Internet’s coin. On one side is the abundance of opportunities that the Internet’s borderlessness creates. On the other side is the insatiable appetite for content that comes with this absence of borders.

In 2020, YouTube saw a 43% surge in video consumption on its platform. The numbers have risen steadily, on mobile especially, in recent years. This consistent demand for content, coupled with the transience of attention, puts creators under pressure to produce constantly. As Olga Kay famously told Fast Company in 2014, “If you slow down, you might disappear.” And many have, for better or worse.

Furthermore, because creators often have to keep producing content to earn income from their work (that is if they want to be successful), this could lead to anxiety over income sustainability, which could very well result in burnout.

The obvious solution is for creators to either reduce the frequency with which they publish or outsource some of the work to capable hands. Still, if, as a creator, you reduce how often you put out content, your audience size will likely drop, and so will your income. The alternative, which is to outsource some of the work, also requires money. How can you make more money if you aren’t producing as much? Or, framed another way, how can you make more money without needing to tie yourself to producing so much that your creative juices run out?

I’m not quite sure if we can ever eliminate burnout. But I think we can handle it better. I think we can set up structures and roadmaps that help us chart the course for a sustainable creator economy where we’re less prone to burnout.

Here are a few ideas:

I think this is the lowest-hanging fruit and perhaps the most popular option. We’ve already seen it play out as more creators explore social commerce, merchandising, consulting, paid communities and events, etc. Any option beyond sponsorship deals and subscriptions is worth considering.

Much like athletes, musicians, and actors, there’s not a single creator who will be hot forever. Therefore, it’s sensible for us to think about ways to formalise and standardise our practice to the point where we can either transition into investors or, instead of always taking fees and commissions, request some slice of ownership from the brands that approach us for deals. This is particularly important for African creators who have built large followings.

Studying global marketing trends will help us understand that we’re at a tipping point in history where influencers (and creators) are becoming essential cogs in the engine of brand marketing. So, it might be a good idea to ask brands for stock options instead of simply accepting cash all the time.

In 2020, Harry Stebbings, host of The Twenty Minute VC podcast, launched a micro fund for $8.3 million in what is one of the most popular creator-to-investor transitions globally. Earlier this year, Stebbings raised an additional $140 million. While there is no guarantee that his skills as a podcaster will serve him well as an investor, his transition does point out what is possible.

Creating content and making money from it doesn’t preclude you from leveraging your network and using that to build a more sustainable financial future for yourself. There are many more examples of creators becoming investors, and we will likely see more in the near future. I’d particularly like to see more examples in Africa. Beyond investing as a venture capitalist, you can become a talent scout for more creators, provide them with seed funding, and earmark a portion of their revenue as your return on investment.

Data will increasingly influence the movies and TV shows of the future. (It already does now, but even more so in the coming years.) Right now, this plays out in the form of studio remakes and influencer-driven casts. But I imagine there will be a time soon where movie studios will resort to taking skits and creator ideas and building bigger storylines around them. Or perhaps a time when we see podcasts and newsletters grow into larger experiential concepts than their initial artform. Before that time comes, however, creators (again, particularly those in Africa) need to invest more in intellectual property protection. As Western corporations have shown us, nothing is too ridiculous or insignificant to copyright.

There’s no better time in history to be a creator than now, especially if you live in an emerging economy. You’re no longer bound by geography and the stringent economic realities of your market. We’ve recently seen African digital artists make thousands of dollars by listing their art as NFTs (examples here and here). But digital paintings and images aren’t the only things that can be minted as NFTs, articles can be too. This opens up a new world of opportunities that scarcely existed on such a massive scale before. To understand what NFTs are and why they’re so revolutionary, start with this explainer.

I don’t intend to shut down this newsletter anytime soon. But I’m seriously thinking about its sustainability. For something that relies heavily on the quality of insight, I plan to spend the next few weeks trying to answer some of these questions: How do I keep up Communiqué + my day job without burning out? How do I preserve the essence of this publication so I can continue serving you to the best of my ability, even if it means shedding most of the load? Thankfully, this process will become easier with Substack’s help through its Grow Fellowship, which I’m a part of.

As 2021 winds down, allow me to ask you for a favour, please. Reach out to all the creators that have made your year worth it. Send them “Thank You” notes. Send them kind and gentle messages of encouragement. And if possible, buy them gifts.

Being a creator is hard, even if it doesn’t always look like it, but it’s worth it when the people we create for appreciate us for what we do.

Thank you, and see you in 2022!

]]>

It’s May 2021. I’m watching a gadget review video on Marques Brownlee’s YouTube channel, MKBHD, when I notice an icon beside the “Subscribe” button. It reads “Join”. Curious, I click.

Up pops a window asking me to “join this channel” and “get access to membership perks”. One of those perks is access to behind-the-scenes content from one of the most excellent YouTube channels. MKBHD has accumulated a massive audience, so I imagine many of his 14.8 million subscribers will be interested. Just not me.

MKBHD already makes money through YouTube ads, affiliate marketing, brand sponsorships, and selling merchandise. This membership feature is another way for him to monetise his channel. If 1% of his subscribers sign up, he’ll generate additional monthly revenue of nearly $200,000. Even if only 0.5% sign up, that’s close to $100,000 a month. But MKBHD is unique because most YouTubers won’t make nearly as much from all their income sources combined.

Yet, YouTube is one of the more generous platforms for creators. It gives them 55% of revenue from ads placed in their videos through Google AdSense and has paid out $30 billion in the last three years. In May 2021, it announced a $100 million creator fund for YouTube Shorts, its Tik Tok rival feature.

But as generous as YouTube is, it’s still not the most lucrative income source for African creators, many of whom cannot subsist on ad revenue from their videos alone. They have to depend on brands for sponsorship and advertising deals or funnel their audience into other businesses.

One of the most significant determinants of YouTube ad revenue is the country where the audience is from. As Nigerian YouTuber Tayo Aina explains, if you make a travel video where most of the audience is in the US, you’d generate far more income than if most of the audience is in Nigeria.

In theory, the Internet gives us access to a global audience. In reality, this isn’t always the case. More often than not, for African YouTubers (and creators), their content will mostly be consumed by a local audience. That means they can’t generate as much as they’d like from ad revenue because of their audience’s location. It also means they’ll need to amass large followings before brands even consider them for partnerships.

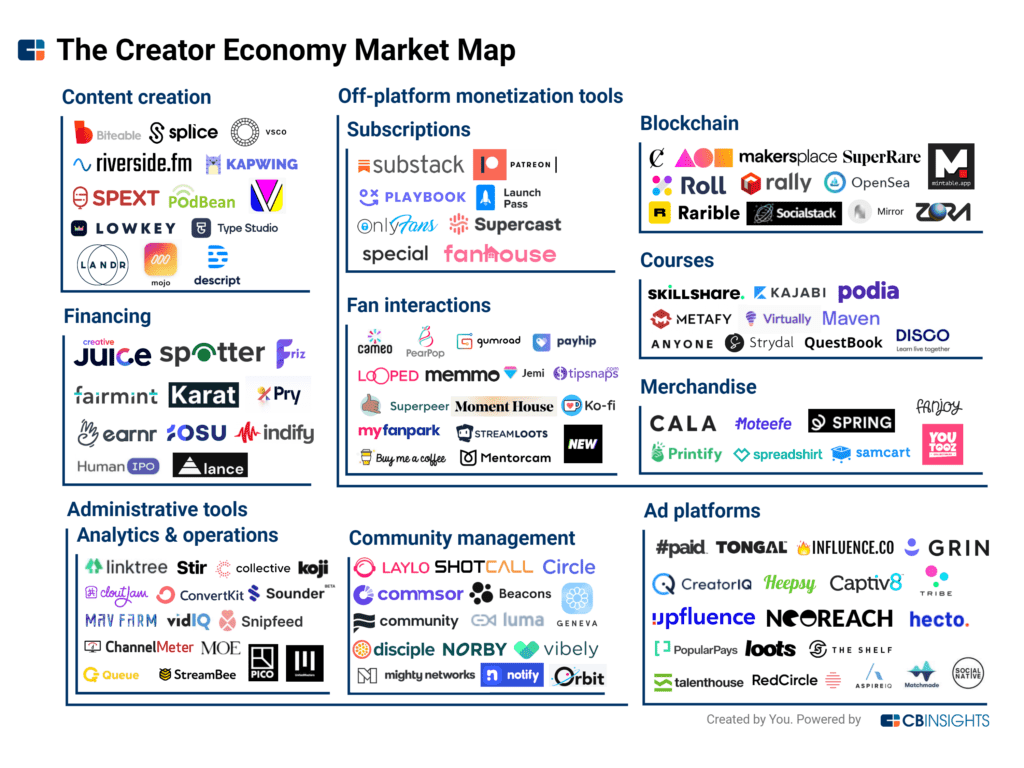

This over-reliance on brands for money got me thinking about the evolution of the creator economy in Africa. (The creator economy is an ecosystem of writers, videographers, social media influencers, gamers, podcasters, skit makers, etc., and the software tools and platforms that enable them to build an audience and potentially make money.)

The conversation about this ecosystem is happening worldwide, but there’s a conspicuous omission of its formulation in emerging markets. Despite its global implications, the conversations are louder in some regions than in others.

We’ve seen this happen before. It happened with the creation, evolution, and monetisation of mass media. It happened with the creation, evolution, and monetisation of the Internet. It’s happening with the creation, evolution, and monetisation of social media and creator platforms. It doesn’t have to continue.

In this essay about the Latin American creator economy, Julio Vasconcellos, managing partner at Atlantico, a Latin America-focused VC fund, writes that independent creators and influencers have become a force in the region. But it’s still tough for them to translate their social capital into cash. He references a survey of more than 5,000 creators in Brazil, which showed that half of them made less than $100 per month, and nearly 25% of them didn’t monetise at all.

This assessment sounds somewhat similar to the plight of creators on this side of the world. But while there is already a sizeable amount of successful creators (YouTubers, online comedians, beauty vloggers, etc., who make money from their craft), there is no systematic path to success.

Still, the creator economy, already worth over $100 billion, is taking off globally. But it seems like Africa is an afterthought in formulating the frameworks for thinking about it.

There are extensive conversations around monetising and standardising the business ecosystem for creators. But these conversations happen predominantly in the West.

If these critical conversations happen predominantly in the West, it follows that innovation will mainly happen there. As with many other things, the products of that innovation will eventually trickle down to this part of the world. But by then, the ideas and solutions will account primarily for Western cultural and economic contexts while excluding the nuances of being a creator elsewhere.

Let’s use Substack as an example. I’ve been publishing on this platform for a year and a half now and have made no money from it. But assuming I wanted to monetise this newsletter, I’ll face two problems.

The first is payment-related. Substack is a universal platform, but its payment processor, Stripe, isn’t available in Nigeria (yet). Even if I wanted to accept payments from my subscribers right now, I wouldn’t be able to. I’d have to get an American bank account as Joey Akan, publisher of Afrobeats Intelligence, did.

Payment is essentially a regional play, and it’s difficult to build a universal solution because government regulations can be restrictive. (Crypto solves this problem, but that is a conversation for another day.)

The second problem is that of economic reality. As I explain in ‘The subscription playbook’, “By asking your audience to pay for content, you are competing with the necessities of life – food, shelter, health, leisure, etc. It’s tough when most people don’t have substantial disposable income. What’s more? The number of people who do is paltry.”

So, while Substack solves my publishing and distribution problems, it poses a different challenge once monetisation comes up. The same goes for millions of other African creators. Creating and distributing content is easy. Monetisation is hard.

Furthermore, because disposable income is low in many African countries, it is difficult for creators to directly make money from their audience.

For this reason, they have to depend on brands for advertising and sponsorship deals. This is not necessarily bad, but it is fragile. Creators are only as relevant as the buzz they generate, and every serious creator knows they won’t be hot forever. Depending on brands for sponsorship deals also means creators have no ownership or equity. They are entirely at the mercy of the entities that pay them for promoting their products and services.

In summary:

Monetising content as an African creator is hard, partly because several payment-related problems exist.

It's also hard because disposable income is low in many African countries. This makes it difficult for creators to monetise their audience directly.

Creators have to depend on brands for advertising and sponsorship deals. This option is fragile because it means they have no equity and their income is tied directly to their output, putting them at the mercy of the entities that pay them.

To open up Africa’s creator economy, we must expand the pool of financial resources and empower creators to think more strategically and deliberately about their business. We must make it easier for them to make money and for people to invest in the creators they care about.

But how do we do that?

Fix the payment problem.

According to Paystack’s Storefront data, in the first half of 2021, eight out of the top 20 bestsellers on the platform were digital products or professional services and courses. Also, 10% of the 100 bestselling merchants on the Nigerian Storefront were consultants or content creators who sold digital products.

This is just one use case out of many which prove that fixing payment problems opens the gateway to infinite opportunities. In this case, it provides a platform for creators to layer several things on.

Think about how Paystack now helps local merchants to collect payments from Apple Pay users. Or how Flutterwave helps African merchants collect and send money through Paypal. Creating local solutions like these connects us with global opportunities that make it easier for African creators to make money from their work. It also encourages global platforms to partner with proven local players.

In 2020, fintech funding in Africa crossed the $1.3 billion mark. Some argue that the market for fintech startups is oversaturated. Others say that we need even more funding to solve all payment-related problems. I fall in the latter category. There are gaps for local and niche payment solutions that will ultimately be consolidated as the market expands.

Build more creator-friendly commerce infrastructure.

One of the things I talk about in ‘The subscription playbook’ is that content is not enough. Africa is a heavily utilitarian market, which means most people are more concerned about the benefits that come with paying for something than they are with the intrinsic value of that thing.

Most creators won’t make money purely from their content. They will need to integrate other benefits or businesses. An example is South African fashion content creator Lesego Legobane (also known as Thick Leeyonce). Legobane creates content to promote body positivity and has a large following online, which she then channels into her fashion line, LeeBex.

Creating content and running a business require different kinds of expertise. Therefore, there is room for platforms that take most of the burden of commerce off the creator’s shoulders. Selar and Africreators solve a part of this problem by building platforms for creators to sell digital and physical products, but there can be more.

Expense tracking, process automation, and logistics are all hurdles that need crossing. Currently, there are primarily fragmented solutions, but perhaps there is a gap for an aggregator.

Standardise the creator economy.

The next step is standardisation, and this requires us to think of creator ventures as actual enterprises, not hobbies. Creators should be able to track every part of their business, from cash flow to analytics, logistics, human resource management, and order fulfilment.

This opens up them to new opportunities. It makes it easier for investors and funds who might be interested in certain creators to be able to track or forecast their return on investment. We’ve seen how much more money is coming into the ecosystem and how willing people are to invest in the best creators.

Standardising the ecosystem also requires creating or amplifying specialised knowledge that helps creators better understand the demands and complexities of running a business and optimising operations. All these make them more attractive to investors.

Create access to credit facilities and funding.

Imagine if African creators had access to a fund or unique loan facility that could allow them to build extra layers of business operations on their creative abilities and audience. Imagine if venture funds could incubate creators how record labels incubate musicians (under less draconian conditions, of course). There are many ways to think about this, but all the most viable ideas require a standardised creator ecosystem.

Explore social tokens.

I currently work with the African Tech Roundup, a tech analysis platform, and one of the ways we’re thinking about community building is through social tokens. We’re launching the $ATRU token to reward our most active and engaged community members with exclusive benefits.

There are several other use cases for social tokens. But at their core, social tokens are a way to reward creators directly for their work and strengthen their connection with their audience, making it easier for people to put their money where their mouth is.

There are many other ways to think about the creator economy in Africa. We must begin to have these conversations more openly and loudly. My goal here is not to be definitive but to highlight where the opportunities exist and offer perspective into a movement that is still nascent before it grows too big and leaves us behind.

PS: A big thank you to Fu’ad Lawal and Ope Adedeji for helping me edit and refine this essay.

]]>

Despite being around for more than 20 years, podcasts have still not caught on in Africa. The industry is worth more than $11 billion (up from $9.28 billion in 2019), but that value is concentrated in the US and North America. This is unsurprising; podcasting kicked off in that part of the world in the early 2000s and has seen heavy investment. Significant innovation around content, monetisation, and technology have also contributed to its growth.

In the last decade, podcasts and podcast production have experienced a growing interest in Africa. These podcasts are often inspired by successful shows in the West and adapted for the local audience based on the host’s interests and/or profession. In South Africa, there’s Alibi, the investigative journalism series, and the African Tech Roundup, among others. In Zambia, we have Leading Ladies, an animated podcast series dedicated to women in the country’s history. In Kenya, there’s Cut the Foreplay, a comedy series; Legally Clueless, which is focused on the presenter, Adelle Onyango’s journey as an African woman; and Surviving Nairobi, a podcast based on the lives of its hosts, DJ IV and Hafare. Then there’s Ugandan radio and TV presenter Lee Kasumba’s Africa State of Mind (also defunct).

But despite the moderate success of some of these shows, anecdotal evidence suggests podcasting is still far from popular in Africa. Why?

According to Abe Adeile and Osagie Alonge, both involved in making the famous Loose Talk Podcast and are now co-founders of Visual Audio Times, a podcast network and production company in Lagos, Nigeria, podcasting’s biggest hurdle in Africa is inadequate infrastructure. Unlike radio which is cheap and requires no extra cost to access, podcasts need additional data and specific phone features that many Africans cannot afford.

Alonge parallels podcasting with music streaming:

“It costs you N900 to pay for Spotify or Apple Music for a month. But it’s probably going to cost you two or three times that amount to stream from those platforms because you have to buy data, and data is expensive. That’s why [many] people will not download Spotify because they can’t keep streaming repeatedly. You can always bring up the option of downloading. But then you have to address the questions: “What kind of phone do I have? How much space do I have on my phone?”

Justin Norman, producer and host of The Flip, a podcast that explores "contextually relevant insights" from entrepreneurs in Africa, echoes Alonge’s views. He says:

“If we’re talking about a mass-market African consumer, listening to a podcast takes a lot of data. So it might not be the best means of distribution in comparison with radio or something text-based.”

So, podcasters in Africa have to deal with the high cost of data and inadequate phone features. These challenges affect distribution. But there’s more. Podcasts also have to compete with more accessible media and formats. Most people who listen to podcasts do so on their phones. But if you observe phone usage data, you’ll likely find that people spend most of their time on social media and messaging apps. They interact with videos, images, and short-form text on these social media and messaging apps more than any other format.

I’ll use myself as an example. Here’s what my screen time looks like:

Nevertheless, it’s still worth asking if there are ways around these challenges for the sake of the opportunities that podcasting presents. Think about it:

The industry is already worth more than $11 billion and is expected to cross $60 billion by 2027. That value will end up somewhere. Some of it might as well come to Africa.

Massive investments have gone into podcasting in recent years. Since 2015, we’ve seen huge acquisitions and licensing deals. As I mentioned in the previous edition of Communique, Spotify spent $600 million on podcast-related investments between February 2019 and 2020 alone.

Podcasts present a chance to tell important stories at a fraction of the cost. It costs less to record a podcast than to produce a movie, video documentary, or even publish a book.

If a podcast is thriving and has a large audience, it can be adapted into other formats. Aaron Mahnke’s ‘Lore’ is a classic example. He struggled to sell his books, so he recorded a podcast telling historical tales of the dead. They were low-budget productions that attracted 5 million listeners per month. The podcast was eventually adapted into a TV series. Of course, this is just one example, but it embodies what could be.

Finally, the future of audio is on-demand, and podcasting is currently the most popular form. Even if podcasting is not the future itself, it plays a significant role in how we get there.

Writing about Spotify’s entry into Africa, I suggested that we focus instead on its overall gameplan:

“If you think about Spotify purely as a music streaming service, I can excuse you for failing to see why its entry into the market is a big deal… But this goes past just another music streaming platform entering into the market. Spotify’s real gameplan is owning your passive media experience via audio. It is gunning for the whole nine yards—music, podcasts, audio advertising, audiobooks, and whatever else technology can conjure.”

In the past, it was harder to discover podcasts if you weren’t already a consumer because podcast apps were standalone. More people listen to music than podcasts, and to do this, they often have to use separate apps. Spotify has blurred the line between what people love listening to and what they can be listening to. Now, you have podcasts and music on the same platform, and that significantly increases discoverability. YouTube does the same for video podcasts.

So, knowing all this, we have to explore realistic ways to grow the podcasting audience in Africa. And the foundation of this is to understand user behaviour better.

It’s 2017 (or 2016, I forget which exactly). I’m sitting in a danfo. Beside me is a man with the base of his phone to his ear. He’s been listening to something for over 10 minutes now. If I pay closer attention, I might hear every word, but I don’t. I only hear enough to recognise what it is — a voice note. Not just any voice note; it’s a type I’m all too familiar with and have grown to hate. My parents send it to me occasionally. Yours probably do, too.

I can’t count how many times I’ve gotten voice notes from my mother warning about impending doom. This is how it happens: someone creates these lengthy recordings saying something controversial and distributes them through the WhatsApp groups our parents belong to. Our parents, thinking they have stumbled on something prophetic or some secret information the powers that be are hiding from us, forward it to as many people as they can. Unfortunately, we are on their contact lists, so we suffer the ignominy of getting these funny messages. Unless, of course, we dare to block them. We don’t have the audacity, though, do we?

Anyway, sitting beside this man for the duration of our very uncomfortable trip, I am fascinated by how at ease he seems with what he is doing. Beyond my fascination, though, I don’t think too much of it. However, years later, as I research more about how to scale and monetise different content types, my mind goes back to that day. Seeing that man so conveniently listening to a voice note the length of a podcast episode in a crowded bus prompts me to look closer at how user behaviour should influence content creation and distribution.

Looking at the challenges podcasting faces is essential, but they don’t tell the whole story. They don’t explain why the man sitting beside me on the bus that day was so comfortable listening to what is essentially a podcast episode on WhatsApp. They don’t explain why so many Africans stream/download church sermons, which also are essentially podcast episodes. Podcasting’s limitations in Africa go beyond just the infrastructural deficit.

If people already spend most of their screen time on social media and instant messaging, then podcasters need to do a better job of meeting people where they are instead of just creating for their podcast platforms. Writers and video creators do this well. They make their videos and publish their articles on native platforms, but they know that isn’t enough. They have to share their content on social media, where most of their audience spends their time. This is not all, though. The most successful writers and video creators also know to adapt their content per platform and create conversations around that content or insert it into relevant conversations.

I’m not just talking about sharing links to your podcast on social media but also adapting it to each platform to optimise distribution. This plays out in the following ways:

Create visual snippets of your podcast and include subtitles in the video. (Here is an example from The Economist.)

Create WhatsApp or instant messaging groups around your podcast and share short audio clips as voice notes (much like our parents already do). This works perfectly if you already have a sizable audience. (An example is Uk’shona Kwelanga, a South African drama series shared exclusively via WhatsApp.)

Build a newsletter community around your podcast. Newsletters are one of the easiest ways to engage directly with your audience, especially when you send show notes in the email so people can quickly see what each episode is about before deciding if/when to listen.

However, all of these must lead back to your primary content, the podcast, and a platform you own. Your social media audience is not yours, it belongs to Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc., and anything can happen to your account at any time. But if you own the platform and your database, the odds are in your favour.

Podcasting can learn from radio’s success. It’s the most popular medium in Africa now, but it was not always the primary way humans consumed audio. In the 1880s, people listened to the news, music, weather reports, etc., via telephones. Radio transmission began in 1906, and the first radio station started broadcasting ten years later. The first recording of a radio broadcast in Africa was in South Africa in 1923 — Felix Mendelssohn's ‘Auf Flügeln des Gesanges’ (On Wings of Song). Since then, the medium has adapted to meet the needs of mass audiences in Africa.

Over the years, radio became the most significant medium in this part of the world for the following reasons:

The barrier to entry is low. As I mentioned earlier, radios are cheap and require no additional cost for access. Once you buy a radio set, you don’t need to spend anything extra to listen to broadcasts with it. This enables the high level of distribution and deep penetration that no other medium has.

Radio stations (and presenters) have figured out how best to engage their audiences. Through local language broadcasting, which breaks down linguistic barriers, and community programming, which covers issues that hit close to home, radio offers a particular type of content that people can’t get anywhere else. This makes it so personable that audiences tune in and feel like their radio station “gets” them.

Finally, because radio stations are so connected to their audience and the grassroots, they know the importance of creating programmes that resonate with people. For example, radio dramas that discuss community-related issues are a big hit and help deliver important messages in engaging ways.

Look away from the West and focus instead on what your people want. Many of the early podcast creators in Africa were either inspired by Western content or the success of certain podcast types and formats in the West. This is understandable. But learning from radio’s success demands that we instead look closer to home. We must understand what our people are already listening to and build on that. Perhaps podcasting in local languages may not be the way to go, but creating content relevant to people’s quotidian activities and hits close to home will be far more effective.

Build on successful radio programmes. We can build on successful radio programmes with massive local audiences by turning them into podcasts and directing people to listen to those podcasts. Nigeria Info FM does this well by converting some of its most successful talk shows into podcasts that people can listen to on its website.

Make possible through podcasting the things that are impossible with film. According to the veteran broadcaster Lindsay Barrett, in the years after Nigeria’s independence, radio dramas were considered an “innovative and exciting medium of creative expression”. But their popularity has waned because they’re capital intensive. Despite their cost, they were cheaper to make than films, and they told the same kinds of stories. With podcasting, they can regain their social status (this time as audio dramas) and share with the world the African stories that we have for so long desired to tell.

I can’t shake this question off my mind: do podcasts really need to scale? Are they that important?

The answer is complicated. Podcasts are a way to broadcast on-demand audio, which is what is really important here. The world is moving away from linear programming to on-demand content, and podcasting is one way that is happening. Africans may not listen to podcasts often yet, but, as we already established, they listen to on-demand audio. (Remember that man sitting beside me on the bus? Yes, he is a sample size of one, but he represents the majority.)

On-demand audio is the future, and the earlier we begin to build towards that future (with deliberate investments into content distribution, Internet infrastructure, and understanding user behaviour), the better. If podcasting is how on-demand audio will scale, then we have to pay more attention to it. But if it isn't, if other channels align more with preexisting behaviour, we should pay closer attention to them.

Remember: radio was not always the primary way we consumed audio content. It will not always be the primary way we consume audio content. The future may seem far off, but it really is closer than we think, and we must be ready for it.

PS: I’d like to thank the people who helped make this essay what it is. Thank you to Akachi Ogbonna, Hassan Yahaya, Fu’ad Lawal, and Ope Adedeji for helping me edit and strengthen my points.

Thank you to Osagie Alonge, Abe Adeile, and Justin Norman for lending their expertise and sharing their experience with me.

If you like this newsletter, then subscribe here:

]]>